Cannabis is by far the most commonly used ‘recreational drug’ in the world. According to the 2017 edition of the United Nations’ World Drug Report, the number of people that used cannabis is around 183 million but that number could be as high as 238 million people worldwide.

Being an integral part of everyday life has led to many other words being used to describe the Cannabis plant, such as weed, pot, ganja or grass. The number of different phrases and words to describe the cannabis plants is huge and there’s hardly another substance that has so many names. America Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) has even compiled the list of the slang words used for weed and although some of those words are clearly made up and some of them don’t refer to the plants themselves, it shows the wide lexicon people use when talking about cannabis. Lower-case cannabis refers to the plant itself while upper-case Cannabis refers to the genus.

Many names for the same plant

The use of the cannabis plant and its history is global and dates back thousands of years. Over that long period it has carried a variety of identities which is the reason why it has so many names. The word “ganja” comes from Sanskrit, the word “bhang” appears in “The Thousand and One Nights” and “hashish” is used in “The Count of Monte Cristo”.

The slang word “pot” probably comes from the Spanish word for seeds – “potiguaya” and terms like “grass” or “weed” were meant to be poking fun at anti-marijuana propaganda like Reefer Madness. Although, all these different names not-necessarily refer to the cannabis plant itself but to a wide range of cannabis products and derivatives, such labelling makes it difficult to determine how cannabis itself manifests in different historical accounts.

The origins of Cannabis

The word Cannabis is the scientific name given to the plant Cannabis Sativa L. and its variants and it comes from the earlier Greek word κάνναβις. Up to the beginning of the 20th century the word cannabis was solely used when talking about the plant and the word marijuana didn’t exist in the American culture. Most of the pre-1900 references relate to its medical usage or its role in various industries such as textile and rope. It was often referenced as a medicine and a remedy for most common household ailments.

Throughout the 19th century, the word “cannabis” was used when referring to the plant and U.S. scientific journals published hundreds of articles touting the medicinal and therapeutic properties and uses of cannabis. So much for not knowing the long-term effects and being poorly researched – an excuse often used by modern time prohibitionists and opponents of the plant. From 1850 to 1937, cannabis was used as the prime medicine for more than 100 separate illnesses and diseases in the U.S. Pharmacopoeia.

Up till then, what’s now considered ‘recreational use’ of cannabis was almost non-existent but some trends of experimenting with cannabis existed, especially among the wealthy elite that could afford imported goods. Use of cannabis was popularized and glamorized by various celebrities such as Alexander Dumas, a member of the “Hashish eaters club”, which, among others, included Victor Hugo, Charles Baudelaire, Honoré de Balzac and Gérard de Nerval.

The Mexican origin

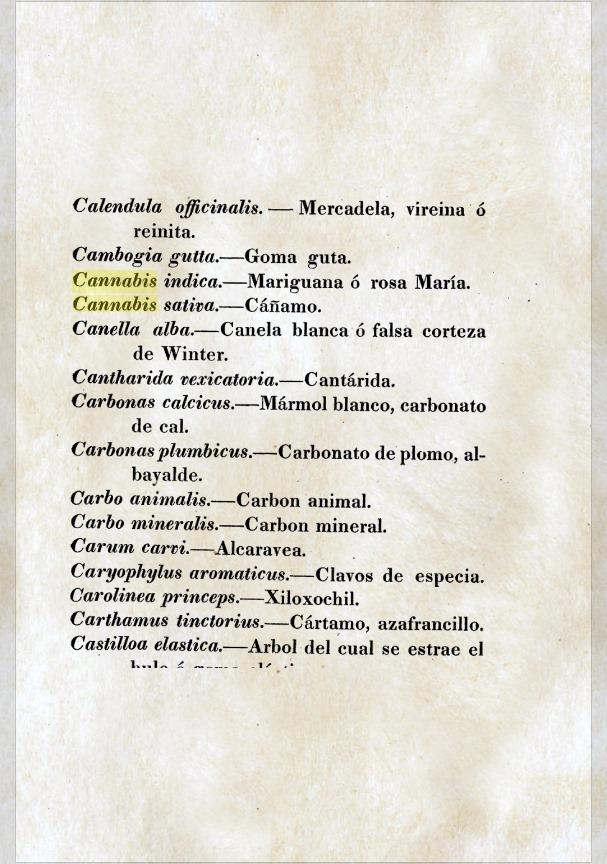

Pharmacopoeia Mexicana showing marijuana / mariguana being listed almost a hundred years prior to Reefer Madness

When spanish conquistadors and other european settlers arrived in present-day Mexico they brought cannabis plants with them. Prior to that, cannabis was not present in the Americas. The Europeans ordered the indigenous residents to stop growing their own psychoactive drugs, which up till then, were commonly used in everyday lives. Plants such as peyote, psilocybin and morning glory were an integral part of various religious ceremonies which were also banned in an attempt to convert them to Christianity.

Mexicans were told to grow cannabis plants for rope but they soon discovered that the plants themselves could be psychoactive. To hide the ‘recreational’ use, they started to ‘code’ the languages and changed the name into what became ‘marihuana’. A common practice of putting “mary” in the name was to please the Spanish and were used on many other plants as well.

There are many other theories of how cannabis came to be marijuana – one says that the Chinese immigrants lent the plant its name – coming from the combination of syllables that may have referred to the plant in Chinese (ma ren hua). The other one saying that it’s a colloquial Spanish way of saying “Chinese oregano” — mejorana (chino). The third one says that maybe Angolan slaves that were brought to Brazil carried the Bantu word for cannabis ma-kaña with them. Other theories say that the word originated in South America itself, as a combination of the Spanish girl’s names Maria and Juana but as the plant was not native to Mexico, a native source for the word seems unlikely.

No matter of the origin story, the term, originally spelled variously as “mariguana” or “marihuana” originated in Mexican Spanish and was widely used in Mexico at least hundred years prior to its use and bastardization in the US. The term, as well as the plant, was becoming more and more popular among the Mexican population and is even used in popular Mexican Revolutionary era song La Cucaracha, describing its use by Mexican soldiers.

| Spanish | English |

| La cucaracha, la cucaracha, | The cockroach, the cockroach, |

| ya no puede caminar | can’t walk anymore |

| porque no tiene, porque le falta | because it doesn’t have, because it’s lacking |

| marihuana que fumar. | marijuana to smoke. |

The first known appearance of the word marijuana in English, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, dates back to 1873 and the publishing of “The Native Races of the Pacific States of North America” by Hubert Howe Bancroft. Other early variants include “mariguan”, “marihuama”, “marihuano” and “marahuana” date back to 1894, 1905, 1912 and 1914 respectively.

How it all started to turn sideways

The political upheaval in Mexico, that culminated in the Mexican Revolution, brought over 890,000 Mexicans seeking refuge into the states throughout the American Southwest. And although cannabis had been a part of US history since the country’s beginnings, “recreational” use was not as common until the arrival of immigrants who brought the smoking habit with them.

The United States were starting to feel the effects of what came to be known as The Great Depression and Americans were searching for someone to blame. Similar to what’s happening now, they directed their prejudices and fears towards Mexican peasant immigrants and extended them to their means of intoxication, which was smoking marijuana – a habit that was also used by many black jazz musicians.

Stories claiming that cannabis incited many violent crimes started to emerge and various claims about cannabis, such as that it aroused the lust for blood or giving its users superhuman strength started to appear in the media. As a result, many white Americans started to treat cannabis and, arguably, the black and Mexican immigrants who consumed it, as a devilish substance, used to corrupt the minds and bodies of low-class individuals.

Reefer Madness

We would love to hear your comments on this!

The original 1936 anti-drug propaganda film

Anti-drug campaigners of the early 20th century started using the phrase “marijuana menace” in their smear campaigns to describe the imagined onslaught of cannabis-related crimes. It was meant to play off of anti-immigrant sentiments and was directed primarily towards Mexican immigrants. Mexican slang term “marihuana” was used to highlight the drug’s “exotic” and more sinister origin, taking jabs at the Mexicans that brought its use to the US, as well as to separate it from the otherwise widely accepted medical use.

The term made the plant sound foreign and scary and it fed into the growing racism and xenophobia. This disparity between “cannabis” mentions pre-1900 and “marihuana” references post-1900 made it almost as though the papers were describing two different drugs. Anti-cannabis campaigns were starting to rise and many magazine ads and movie theaters warned the general public about the marijuana’s tendency to make marijuana users go crazy. Many short propaganda films showed Mexicans going violent and crazy from their marijuana cigarettes, terrorizing Western ranches and white population.

Among two of the most vocal prohibitionists were Harry J. Anslinger – the first U.S Narcotics Commissioner and media mogul William Randolph Hearst. The two rallied against hemp in favor of synthetic fibers like rayon and nylon and against the use of hemp in the paper industry, in which they heavily invested in. Most household items at the time were made from natural fibers, mostly from hemp, and they needed a way to persuade the people to switch onto their products.

Anslinger’s anti-cannabis and racist stance was well known and is well documented. ”Marijuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind,” he said during one of his testimonies. “Most marijuana smokers are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their satanic music, jazz and swing, result from marijuana usage.”

Hearst on the other hand was more of an opportunist, being heavily invested in paper and synthetic industries he saw it as a way of getting rid of the competition. The two spearheaded the anti-cannabis campaign, publishing detailed stories describing the violent and gruesome effects cannabis supposedly yielded while vilifying the people of color. Their “masterpiece” was the 1936 propaganda film Reefer Madness, which introduced African Americans as criminals, claiming they were attacking and sexually abusing white women.

The Marijuana Tax Act

The first anti-cannabis laws were targeted at the term “marijuana” in an effort to marginalize the new migrant population and it is no coincidence that the first US cities to ban cannabis were in the border states. El Paso, Texas was the first US city to ban cannabis, prohibiting the sales and possession of cannabis in 1914.

Anslinger’s crusade succeeded with Congress approving the Marijuana Tax Act in 1937, which effectively criminalized pot possession throughout the United States. The Marijuana Tax Act heavily taxed cannabis and in cases when the tax couldn’t be paid, it meant a prison sentence instead. The high taxes also pushed cannabis out of the medical realm, since very few could afford it.

Mexico banned cannabis 17 years before the US

But according to Ivan Guerra, a professor of Southwest Studies at Colorado College, Anslinger was influenced by elite Mexicans, who also saw the plant as low-class. And according to Isaac Campos, an Associate Professor of History at the University of Cincinnati, the accounts in the American press just echoed the stories that had been published in Mexican newspapers well before.

As he documents in his book “Home Grown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs”, very similar accounts were previously published in Mexico – stating that a soldier was “driven mad by mariguana” and attacked his fellow soldiers (El Monitor Republicano, 1878), that a pot-crazed soldier murdered two colleagues and injured two others (La Voz de México, 1888), that a prisoner stabbed two fellow inmates to death after smoking up (El Pais, 1899) and similar stories.

Although prohibition of cannabis in the US relied heavily on racism and xenophobia, claiming that cannabis was outlawed because of Mexicans is not quite true. Mexico was cracking down on cannabis around the same time as the US and Mexico’s prohibition of cannabis came in 1920, a full 17 years before the US government did the same.

Legal cannabis era

Up until just a few years ago and the decriminalization of cannabis in the United States, term marijuana was widely used. Ronald Reagan who started the “War on Drugs” called marijuana “probably the most dangerous drug in the United States”. Thirty-some years later, Bill Clinton “never denied” his use of marijuana, although claiming that he “never inhaled” and Barack Obama openly admitted his previous marijuana use.

However, amid all the legalization and decriminalization taking part, many industry professionals have started avoiding the term marijuana altogether. As a part of a rebranding effort, many say it’s due time for the plant to detach from its racist and fear-mongering (and not to mention unmarketable) history and to get back to its non-racists roots and its scientific name cannabis.

Getting rid of a word won’t get rid of the stigma

Replacing the term “marijuana” with “cannabis” can’t erase its history and won’t get rid of the stigma that’s attached to the plant itself. “The term should continue to be used so that people have to be reminded about this problematic history and the problematic relationship we have with this plant and the type of relationships that it’s created between different populations,” says Ivan Guerra.

“Changing the hearts and minds of the public with regard to marijuana has always been about substance, not terminology. Reformers are winning the legalization debate on the strength of our core arguments – namely, the fact that legalization and regulation is better for public health and safety than is criminalization — and not because of any particular change in the lexicon surrounding the cannabis plant.” – said NORML Deputy Director Paul Armentano.

“A rose by any other name would smell as sweet”

Researchers at Vanderbilt University partnered with YouGov to survey 1,600 adults in the US in order to assess the public attitude toward “marijuana” vs. “cannabis”. They surveyed the participants on a broad range of questions including legalization, tolerance of drug activities, moral acceptability and perception of harms and stereotypes of users.

According to the survey, 50.1% supported the legalization of marijuana and 50.3% supported the legalization of cannabis. The authors note that the only considerable difference was in how much they support cannabis legalization: 34.3% strongly support “cannabis legalization,” compared to 26% of people who strongly support “marijuana legalization.” Support for legalization also increased when the term “medical” was attached.

“In each and every test, the name frame (‘marijuana’ versus ‘cannabis’) has no impact on opinion toward the drug.”

Ultimately, the authors write, their findings “undermine the notion – widely espoused by policy advocates – that abandoning the word ‘marijuana’ for ‘cannabis’ by itself will boost the prospects for reform or soften public attitudes toward the drug.”

“Medical” cannabis as yet another attempt to rebrand weed

There is no such thing as “medical” cannabis and there’s no such thing as “recreational” cannabis, there’s only cannabis that can be used medicinally or ‘recreationally’. Each and every cannabis plant is medicinal, whether it’s hemp or marijuana and people using cannabis will get those medicinal benefits whether that’s their intent or not.

So… why do we have “medicinal” cannabis or “medicinal” marijuana?

The answer to that question is very simple. Most politicians, whether they were in Congress, Senate or any other public office built their platforms on a “tough on crime” approach. This appealed mostly to the uneducated masses who thought that putting more and more people in jail will make their country safer. In reality, all it did was bring more profits to privately owned jails, prisons and municipalities that they belonged to and the number of crimes continued to grow year by year.

Instead of hunting down real criminals and tackling crippling crime statistics most regions in the United States have, tough on crime, in reality, ment putting away people for petty crimes such as cannabis possession. More people were getting arrested for cannabis possession than for all violent crimes (rape, robbery, aggrevated assault, murder, non-negligent manslaughter) combined. In 2013, in the US the number of arrests for marijuana possession was 609,000 and the number of all violent crimes combined was 480,000.

Various regulations such as the ‘three strike’ rule meant that if it was your third conviction, no matter what you were charged for, you were going to get life in prison. Many people got unreasonably high penalties for non-violent crimes that put them in jail for years, even decades.

With decriminalization and legalization of cannabis coming out of Pandora’s box meant that the genie, that is cannabis, would never go back in the bottle again. That landed most of those politicians in hot water. How could they admit that now cannabis is not only legal but recommended for a variety of conditions, many of whom having no other cure or treatment other than cannabis?

Easy – they’ve put the word “medical” in front, as if that’s somehow a different plant than the one they’ve spent 80 years demonizing. It’s not. It’s the same weed, grass or pot thousands of people used illegally for decades to treat their conditions or just to feel better.

Unfortunately, many cannabis activists accepted the term, thinking that once the medicinal use of cannabis is admitted and accepted, cannabis would be, at least, rescheduled if not descheduled and removed from the Controlled Substance list, effectively removing the prohibition of cannabis.

Well, that was a nice theory but the US government had other plans. With the passing of Proposition 215 in 1996, California became the first US state to legalize “medical” cannabis. Cannabis activists saw that as a huge victory, which it undoubtedly was, and thought that legal cannabis was just a matter of time.

Cannabis was, and still is, a Schedule 1 narcotic, according to the US government, and that means the drug has NO medical value and has a high potential for abuse. Obviously, legalizing weed to be used as medicine goes to support the opposite of that but the same logic isn’t shared with the federal government.

But, the US government didn’t just stop there, they even filed and got the patent for using Cannabinoids as antioxidants and radioprotectants. So, how could the same government hold a patent on using cannabis as medicine and claim that cannabis has no medicinal value? Well, your guess is as good as ours. It makes as much sense as having thirty three states and the District of Columbia passing laws broadly legalizing marijuana in some form or another while keeping it federally illegal – for almost two and half decades later.

Racism isn’t just a word

Although cannabis prohibition undoubtedly lies on racisms and xenophobia, saying marijuana instead of cannabis isn’t racists. Being racists is what makes someone racists and if racists people like Harry Anslinger used any other word to further their agenda, cannabis included, it would have been just as racists as when they used marijuana.

Personally, we couldn’t care less what you call it, as long as you make it legal and available to all those in need. And if anything, people should be saying marijuana instead of cannabis as a reminder that powers that be lied and continue to lie about this remarkable and exquisit plant. It’s not our shame, it’s theirs and we shouldn’t let them get away with it.

Why not head on over to The Vault Cannabis Seeds Store and pick up some cannabis seeds now, whilst taking advantage of the discount codes VAULT15 for 15% of your order total and don’t forget to check out our discount cannabis seeds page for all the latest offers, promos and competitions!

Make sure you never miss another Vault promo and sign up for our newsletter at https://www.cannabis-seeds-store.co.uk/the-vault-newsletter

Remember: It’s illegal to germinate cannabis seeds in many countries including the UK. It is our duty to inform you of this important fact and to urge you to obey all of your local laws. The Vault only ever sells or sends out seeds, or seed voucher prizes for souvenir, collection or novelty purposes.